SurgeMQ: MQTT Message Queue @ 750,000 MPS

Thu, Dec 4, 2014

- Wow, this made front page of Hacker News! First for me!

- jacques_chester on HN has an EXCELLENT comment that’s definitely worth reading. My response.

tl;dr

- SurgeMQ aims to provide a MQTT broker and client library that’s fully compliant with MQTT spec 3.1.1. In addition, it tries to be backward compatible with 3.1.

- SurgeMQ is under active development and should be considered unstable. Some of the key MQTT requirements, such as retained messages, still need to be added. The eventual goal is to pass the MQTT Conformance/Interoperability Testing.

- Having said that, running all publishers, subscribers and broker on a single 4-core (2.8Ghz i7) MacBook Pro, SurgeMQ is able to achieve

- over 400,000 MPS in a 1:1 single publisher and single producer configuration

- over 450,000 MPS in a 20:1 fan-in configuration

- over 750,000 MPS in a 1:20 fan-out configuration

- over 700,000 MPS in a full mesh configuration with 20 clients

- In developing SurgeMQ, I improved the performance 15-20X by keeping it simple and serial (KISS), reducing garbage collector pressure, reducing memory copy, and eliminating anything that could potentially introduce latency.

- There are still many areas that can be improved and I look forward to hearing any suggestions you may have.

- I cannot say this enough: benchmark, profile, optimize, rinse, repeat. Go has made testing, benchmarking, and profiling extremely simple. You owe it to yourself to optimize your code using these tools.

Lesson 1: Don’t be clever. Keep It Simple and Serial (KISS).

Lesson 2: Reduce or remove memory copying.

Lesson 3: Race conditions can happen even if you think you followed all the right steps.

Lesson 4: Use the race detector!

Go Learn Project #8 - Message Queue

It’s now been over a year since my last post! Family and work have occupied pretty much all of my time so spare time to learn Go was hard to come by.

However, I was able to squeeze in an implementation of a MQTT encoder/decoder library in July. The implementation is now outdated and is no longer maintained, but it allowed me to learn about the MQTT protocol and got me thinking about potentially implmenting a broker.

Now months later, I am finally able spend a few weekends and nights developing SurgeMQ, a (soon to be) full MQTT 3.1.1 compliant message broker.

Message Queues

According to Wikipedia:

Message queues provide an asynchronous communications protocol, meaning that the sender and receiver of the message do not need to interact with the message queue at the same time. Messages placed onto the queue are stored until the recipient retrieves them. Message queues have implicit or explicit limits on the size of data that may be transmitted in a single message and the number of messages that may remain outstanding on the queue.

Tyler Treat of Brave New Geek also wrote a good series on message queues that went over several of the key MQ implementations. One specific post, Dissecting Message Queues, is especially interesting because it benchmarks some of the major message queue implmentations out there, both brokered and brokerless.

In that post, Tyler found that borkerless queues had the highest throughput, achieving millions of MPS sent and received. Brokered message queue performances ranged from 12,000 MPS (NSQ) to 195,000 MPS (Gnatsd). While the post showed that the Gnatsd latency to be around 300+ microseconds, in reality it’s probably more like the NSQ in terms of latency due to the sender sleeping whenever Gnatsd is 10+ messages behind. Regardless, hats off to Tyler. Great job!

MQTT

I got interested in MQTT because “MQTT is a machine-to-machine (M2M)/“Internet of Things” connectivity protocol. It was designed as an extremely lightweight publish/subscribe messaging transport.”

According to the MQTT spec:

MQTT is a Client Server publish/subscribe messaging transport protocol. It is light weight, open, simple, and designed so as to be easy to implement. These characteristics make it ideal for use in many situations, including constrained environments such as for communication in Machine to Machine (M2M) and Internet of Things (IoT) contexts where a small code footprint is required and/or network bandwidth is at a premium.

The protocol runs over TCP/IP, or over other network protocols that provide ordered, lossless, bi-directional connections. Its features include:

- Use of the publish/subscribe message pattern which provides one-to-many message distribution and decoupling of applications.

- A messaging transport that is agnostic to the content of the payload.

- Three qualities of service for message delivery:

- “At most once”, where messages are delivered according to the best efforts of the operating environment. Message loss can occur. This level could be used, for example, with ambient sensor data where it does not matter if an individual reading is lost as the next one will be published soon after.

- “At least once”, where messages are assured to arrive but duplicates can occur.

- “Exactly once”, where message are assured to arrive exactly once. This level could be used, for example, with billing systems where duplicate or lost messages could lead to incorrect charges being applied.

- A small transport overhead and protocol exchanges minimized to reduce network traffic.

- A mechanism to notify interested parties when an abnormal disconnection occurs.

There’s some very large implementation of MQTT such as Facebook Messenger. There’s also an active Eclipse project, Paho, that provides scalable open-source client implementations for many different languages, including C/C++, Java, Python, JavaScript, C# .Net and Go.

Given the popularity, I decided to implement a MQTT broker in order to learn about message queues.

Architecture

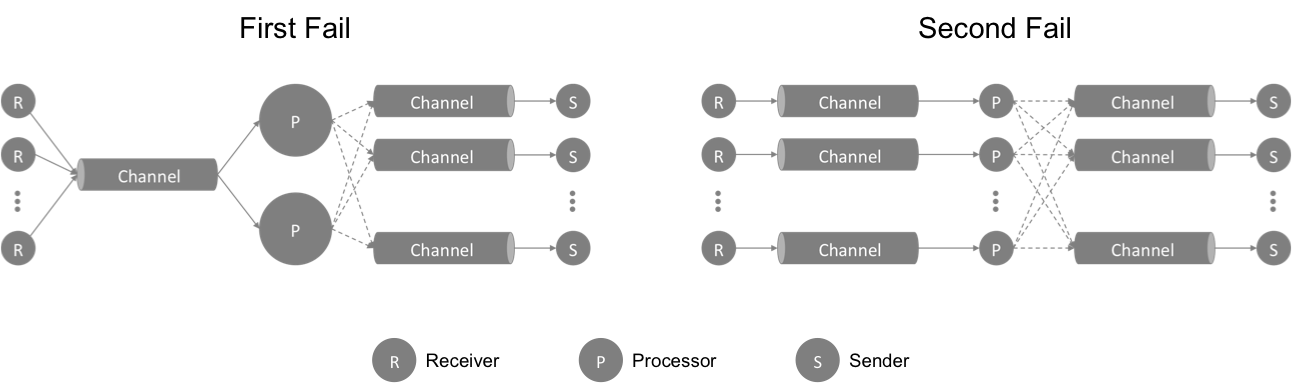

The above image showed a couple of the architecture approaches I attempted. In them, R is the receiver, which reads from net.Conn, P is the processor, which processes the messages and determines what to do or where to send them, and S is the sender, which sends any messages out to net.Conn. Each R, P, and S are their own goroutines.

I started the project wanting to be clever, and wanted to dynamically scale up/down a shared pool of processors as the number of messages increase/decrease. As I thought through it, it just got more and more complicated with the logic and coordination. At the end, before I even wrote much of the code, I scraped the idea.

Lesson 1: Don’t be clever. Keep It Simple and Serial (KISS).

The second architecture approach I took is much simpler and probably much more idiomatic Go.

- Each connection has their own complete set of R, P and S, instead of sharing P across multiple connections.

- Each R, P and S are their own goroutines.

- Between R and P, and P and S are channels that carry MQTT messages.

- R was using bufio.Reader to read from net.Conn, and S was using bufio.Writer to write to net.Conn.

- sync.Pool was used to help reduce the amount of memory allocation required, thus reducing GC pressure

This approach worked and I was able to write enough code to test it. However, the performance was hideoous. In a 1:1 (single publisher and single subscriber) configuration, it was doing about 22,000-25,000 MPS.

$ go test -vv=3 -logtostderr -run=LotsOf -cpu=2 -v

=== RUN TestServiceLotsOfPublish0Messages-2

1000000 messages, 44297366818 ns, 44297.366818 ns/msg, 22574 msgs/sec

After profiling and looking at the CPU profile, I realized there are a lot of memory copying (io.Copy and io.CopyN), as well as there are still quite a bit GC activities (scanblock). On the memory copying front, there’s copying from net.Conn into bufio, then more copying from bufio to the MQTT messages internal buffer, then more copying from MQTT message internal buffers to the outgoing bufio, then to the net.Conn. So lots and lots of memory copying, not a good thing.

Buffered Network IO

The buffered network IO is a good approach, however, there are two things I wished I had:

- bufio shifts bytes around by copying. For example, whenever it needs to fill the buffer, it copies all the remaining bytes to the front of the buffer, then fill the rest. That’s a lot of copying!

- I needed something I can access the bytes directly so I can remove majority of the memory copying.

At this point I decided to try a new technique I learned while doing Go Learn Project #7 - Ring Buffer. The basic idea is that instead of using bufio to read and write to net.Conn, I will implement my own version of that.

The ring buffer will implement the interfaces ReadFrom(), WriteTo(), Read() and Write().

- The receiver will essentially copy data directly from net.Conn into the ring buffer (technially the ring buffer will ReadFrom() net.Conn and put the read bytes into the internal buffer).

- The processor can “peek” a byte slice (no copying) from the ring buffer, process it, and then commit the bytes once processing is done.

- If the message needs to be send to other subscribers, the bytes will then be copied into the subscriber’s outgoing buffer.

While this is not “zero-copy”, it seems good enough.

I started by implementing a lock-less ring buffer, and it worked quite well. But as mentioned in the ring buffer article, you really shouldn’t use it unless there’s plenty of CPU cores lying around. And also calling runtime.Gosched() thousands of times is really not healthy for the Go scheduler.

So keeping Lesson 1 in mind, I modified the ring buffer to use two sync.Cond (reader sync.Cond and writer sync.Cond) to block (cond.Wait()) when there’s not enough bytes to read or when there’s not enough space to write. And then unblock (cond.Broadcast()) when bytes are either read from it, or written to it.

This is a single producer/single consumer ring buffer and is not designed for multiples of anything. The original thought was that since each connection has their own set of R, P and S, there shouldn’t really be a need for multiple writers or readers. It turns out I was wrong, at least on the writer front. We will explain this a bit later.

At the end, this turned out to be the winning combination. I was able to achieve 20X performance increase with this approach after some additional tweaking. Specifically, I tested several buffer block size (the amount of data to read from and write to net.Conn) including 1024, 2048, 4096 and 8192 bytes. The highest performing one is 8192 bytes.

I also experiemented with different buffer sizes, including 256KB, 512KB and 1024KB. 256KB turned out to be sufficient in that it’s the smallest buffer size that doesn’t reduce performance by alot, nor higher numbers will help inprove performance.

Lesson 2: Reduce or remove memory copying.

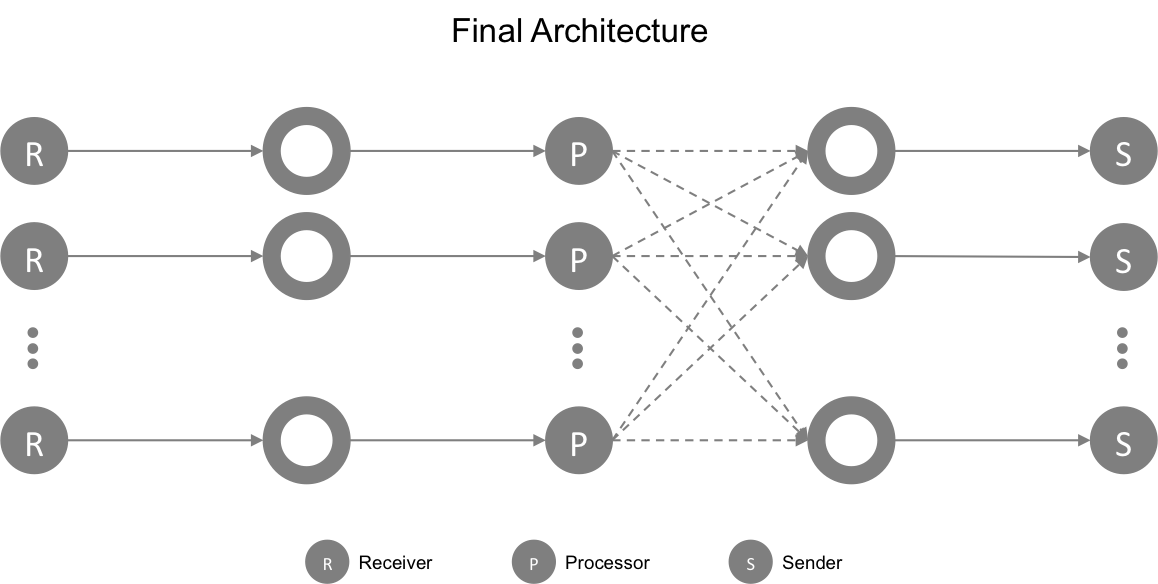

Final Architecture

This the final architecture I ended up with and it’s working very well. The cost of each client connection are:

- 3 goroutines: R (receiver), P (processor) and S (sender)

- 2 ring buffers of 256K each

There’s very few memory copy operations going on, nor is there much memory allocation. So a good outcome overall.

Race Conditions

With the ring bufer implementation, I was able to achieve 400,000 MPS with a 1:1 configuration. This worked well until I started doing multiple publishers and subscribers. The first problem I ran into was the Processor hanging. go test -race also didn’t show anything that could help me.

After running tests over and over again, with more and more glog.Debugf() statements, I tracked the problem to the Processor. It was waiting for space in the ring buffer to write the outgoing messages. I know that’s not possible as I am blasting messages out to net.Conn as fast as I can, so there’s no way that write space is not available.

After running even more tests, and with even more glog.Debugf() statements, I finally determined the problem to be the way I was using sync.Cond. (I wish I saved the debug output..sigh) In the following code block, I was waiting for the consumer position (cpos) to pass the point in which there will be enough data for writing (wrap).

this.pcond.L.Lock()

for cpos = this.cseq.get(); wrap > cpos; cpos = this.cseq.get() {

this.pcond.Wait()

}

this.pcond.L.Unlock()

The steps are really quite simple:

- I lock the producer sync.Conn

- I get the consumer position, compare it to wrap (position that I need cpos to pass to indicate there’s enough write space)

- If there’s not enough space, I wait, otherwise I move on

- I unlock the producer sync.Conn

Then in the Sender goroutine, I read data from the ring buffer, write to net.Conn, update the consumer position, and call pcond.Broadcast() to unblock the above pcond.Wait().

this.cseq.set(cpos + int64(n))

this.pcond.Broadcast()

According to the Go doc,

Broadcast wakes all goroutines waiting on c.

It is allowed but not required for the caller to hold c.L during the call.

So what I have above should work perfectly fine. Except it doesn’t. What happens is that I ran into a situation where pcond.Broadcast() was called after the wrap > cpos check, but before pcond.Wait(). In these cases, the wrap > cpos returned true, which means we need to go wait. But before pcond.Wait() was called, the Sender goroutine has updated cpos, and called pcond.Broadcast(). So when pcond.Wait() is called, there’s nothing to wake it up, and thus it hangs forever.

On the Sender side, because there’s no more data to read, it is also just waiting for more data. So both the Sender and Processor are now hung.

After I finally figured out the root cause, I realized that, unlike what the go doc suggested, the caller should really hold c.L during the call to Broadcast(). So I modified the code to the following:

this.cseq.set(cpos + int64(n))

this.pcond.L.Lock()

this.pcond.Broadcast()

this.pcond.L.Unlock()

What this does is that it ensures I can never call pcond.Broadcast() after pcond.L.Lock() (in the Processor goroutine) is called but pcond.Wait() is not called. When pcond.Wait() is called, it actually calls pcond.L.Unlock() internally so it will allow pcond.L.Lock() in the Sender goroutine to be called.

In any case, we are finally on our way to working with multiple clients.

Lesson 3: Race conditions can happen even if you think you followed all the right steps.

But Wait, There’s More (Race Conditions)

As I increase the number of publishers and subscribers, all the sudden I was getting errors about receiving RESERVED messages, and this happens intermittenly, and only when I blast enough messages. Sometimes I have to run the tests many times to catch this from happening.

It turns out that while I was thinking I only had 1 Publisher per client connection that’s writing to the outgoing buffer, I, in fact, had many. This happens when a client is sent a message to a topic that it subscribes to. In this case, the Processor of the publishing client calls the subscriber client’s Publish() method, and writes the message to the outgoing ring buffer. At the same time, other publishing clients can be publishing other messages to the subscriber client. When this happens, they could overwrite eachother’s message because the ring buffer is NOT designed for multiple writers.

go test -race should technically find this race condition (I think). But given that this condition only happens intermittenly and sometimes it only happens when there’s a large volume of messages, the race detector was taking too long and I was too impatient.

Regardless, after identifying the root cause, I added a Mutex to serialize the writes. At some point I may come back and rewrite it without the lock. But for now it’s good enough.

Lesson 4: Use the race detector!

Performance Benchmarks

These performance numbers are calculated as follows:

- sent messages MPS = total messages sent / total elapsed time between 1st and last message sent for all senders

- received messages MPS = total messages received / total elapsed time between 1st and last message received for all receivers

Environment

$ go version

go version go1.3.3 darwin/amd64

---

Macbook Pro Late 2013

2.8 GHz Intel Core i7

16 GB 1600 MHz DDR3

Server

To start the server,

$ cd benchmark

$ GOMAXPROCS=2 go test -run=TestServer -vv=2 -logtostderr

server/ListenAndServe: server is ready...

1:1

To run the single publisher and single subscriber test case:

$ GOMAXPROCS=2 go test -run=TestFan -vv=2 -logtostderr -senders 1 -receivers 1

Total Sent 1000000 messages in 2434523153 ns, 2434 ns/msg, 410758 msgs/sec

Total Received 1000000 messages in 2434523153 ns, 2434 ns/msg, 410758 msgs/sec

Fan-In

To run the Fan-In test with 20 senders and 1 receiver:

$ GOMAXPROCS=2 go test -run=TestFan -vv=2 -logtostderr -senders 20 -receivers 1

Total Sent 1035436 messages in 2212609304 ns, 2136 ns/msg, 467970 msgs/sec

Total Received 1000022 messages in 2212609304 ns, 2212 ns/msg, 451965 msgs/sec

Fan-Out

To run the Fan-Out test with 1 sender and 20 receivers:

$ GOMAXPROCS=2 go test -run=TestFan -vv=2 -logtostderr -senders 1 -receivers 20

Total Sent 1000000 messages in 10715317340 ns, 10715 ns/msg, 93324 msgs/sec

Total Received 8180723 messages in 10715317340 ns, 1309 ns/msg, 763460 msgs/sec

Mesh

To run a full mesh test where every client is subscribed to the same topic, thus every message sent w/ the right topic will go to ALL of the other clients:

$ GOMAXPROCS=2 go test -run=TestMesh -vv=2 -logtostderr -senders 20 -messages 100000

Total Sent 2000000 messages in 51385336097 ns, 25692 ns/msg, 38921 msgs/sec

Total Received 40000000 messages in 51420975243 ns, 1285 ns/msg, 777892 msgs/sec

Next Steps

There’s a lot more to do with SurgeMQ. Given the limited time I have, I expect it will take me a while to get to full compliant with the MQTT spec. But that will be my focus, now that performance is out of the way, as I get time.

comments powered by Disqus